As the reviews came trickling in yesterday of Monday night’s Julietta at ENO, I have to admit to

wondering if I had just been in the wrong mood, or just hadn’t got where the

greatness of Martinů’s ‘rarely performed masterpiece’ lay. Indeed, was I just

being too cynical in detecting a certain irreconcilable contradiction at the

heart of such marketing rubric? Isn’t it often the case that many of these ‘masterpieces’ rely on their very status as ‘rarely performed’, giving their

champions the convenient riposte: ‘well, you can never really judge it unless

you see it in a decent staging’.

Well, Julietta has

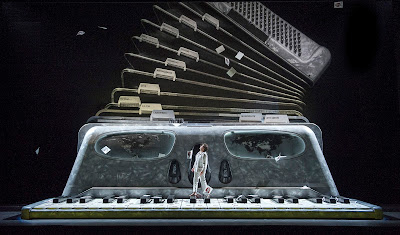

now definitely received that at ENO, with Richard Jones turning in a typically stylish

production—although was I alone in wondering whether, beyond its striking,

stretched and manipulated giant accordion, there wasn’t room for more in the

way of dreamy imagination? The fine cast did an excellent job, the orchestra,

too. And, while I should declare that Monday night was the first time I heard the

score, it seemed as though Ed Gardner made a persuasive case for it: its

splashes of glittering colour came across well, as did the lyrical

outbursts, some of which came close to sweeping me along.

|

| From left to right: Emelie Renard, Clare Presland and Samantha Price as the Gentlemen and Peter Hoare as Michel (Photo: Richard Hubert Smith) |

But the work, based on a surreal play by Georges Neveux,

left me entirely cold. It is neither terribly funny, nor, to our (or my, at least) jaded

21st-century imaginations, terribly interesting. An exploration of a community

floating around in a state of collective amnesia has possibilities for highlighting humour

or a sort of nightmarish, recurring futility, neither of which were explored. Meanwhile,

the work’s leaden pace—lingering on matters with which, by definition, it is

difficult for the audience to engage in any meaningful way—made the 50 minutes

of Act 2, in particular, seem extremely long.

It measures pretty low on the surrealism scale, in any case, and suffers by not employing the sort of snappy pace—a playful, light engagement with time that deals in seconds rather than minutes—that would seem to be part and parcel of the aesthetic, where one flitting absurdity dissolves into the next before the brain has a chance to pin it down and destroy it with logic. A work that came to mind was Shostakovich’s The Nose—hardly a masterpiece, but a piece whose increasingly ridiculous scenes are rattled through at such a pace that they never overstay their welcome. And, of course, we can only have a fragmentary, patchy idea of the actual romance between Julietta and Michel, a travelling salesman who arrives in the strange amnesiac town with the advantage of a memory—an advantage that he, too, finally loses.

It measures pretty low on the surrealism scale, in any case, and suffers by not employing the sort of snappy pace—a playful, light engagement with time that deals in seconds rather than minutes—that would seem to be part and parcel of the aesthetic, where one flitting absurdity dissolves into the next before the brain has a chance to pin it down and destroy it with logic. A work that came to mind was Shostakovich’s The Nose—hardly a masterpiece, but a piece whose increasingly ridiculous scenes are rattled through at such a pace that they never overstay their welcome. And, of course, we can only have a fragmentary, patchy idea of the actual romance between Julietta and Michel, a travelling salesman who arrives in the strange amnesiac town with the advantage of a memory—an advantage that he, too, finally loses.

That’s clearly one of the work’s main points, but whether or

not it inspires deep contemplation or an eye-rolling sense of ‘so what?’ seems more

down to the individual than is often the case, as reviews ranging from five,

through four, to three stars would seem to make clear; from raves to what might

best be called non-raves. Martinů’s score, for its part, has some fine moments, and is put together with considerable skill; but it seemed to wheel out influences with too little input from the composer himself, and, for a work first performed in 1938, seemed distinctly behind the curve—a sense only emphasized by the fact that the production was being supported by

‘ENO’s Contemporary [!] Opera Group’. Still, there are plenty of opportunities for those who haven

’t seen it yet to make up their own minds.

For me, yours is the most convincing argument among the 'cons': I'm very much among the 'pros', as you know, but here's fresh food for thought. I carried on thinking it over in blogland, too, but I still think it's a masterpiece of its own, unrepeatable kind.

ReplyDeleteAs for the sparseness of the staging beyond the reconstituted piano-accordion, my guess is that Jones wanted it all to be pared down to the acting and the movement. Photos of the production in its previous incarnations show that there was more in the way of projected visuals.

Hugo,

ReplyDeleteMy apologies for being off topic but this past June the Zurich Opera House staged Hindemith’s great work Mathis der Maler. There were 7 performances. The title role was sung by Thomas Hampson (his debut) and Daniele Gatti conducted. A real highlight on the opera calendar for sure and yet it received depressingly little coverage.

There was nothing in any of the main broadsheets (Guardian, Times, Telegraph, Herald Tribune). Not even the opera forums (i.e. Parterre Box) made note of the omission. But what is truly inexplicable to me is the fact that the 3 leading magazines -- Opera News, Opera Now and the venerable Opera UK also chose to ignore it. There is not A SINGLE WORD on this major and rarely performed masterpiece or its star cast.

The website OperaCritic.com which usually provides about 10 reviews on average for each opera posted only 4 (yes 4!) entries. And these were mostly by freelance critics.

This entire situation is so ridiculous.

Why does it seem like editors and critics wish to keep Hindemith’s great opera from receiving the exposure it so clearly deserves?

David, thanks for your message, and glad you find my thoughts interesting, even if my reaction to the piece was different to yours. And, as I hope I made clear, this was the opinion of someone not as yet terribly well versed in Martinu; I can well imagine that the piece will grow on me as I familiarize myself with him more. It's interesting, too, what you say about the production. I wonder whether Jones himself, on getting to know the work more, increasingly felt that it could communicate on its own, gradually reducing his own input to allow it to do so...

ReplyDelete@Wistful Pedestrian, I think Hindemith remains strangely untrendy, and might still be tarnished by his 'complicated' relationship to Nazi regime in the 1930s (I've coincidentally just started reading Michael Kater's chapter on him in his rather knotty 'Composers of the Nazi Era', which will hopefully unravel or elucidate some of those complications...). It certainly seems unfortunate, though, that this Zurich production received such short shrift. I can assure you, however, that at OPERA at least there's no anti-Hindemith policy; I think with one thing and another, it was just not possible to get a writer there.

Hugo, I don't have your e-mail, that's why I'm writing here.

ReplyDeleteMy name is Jonas Lopes, I’m a journalist from Brazil. I work at Veja São Paulo (vejasaopaulo.com), a weekly magazine — the biggest of Sao Paulo. I’m writing for you because I’m preparing a cover story about the present moment of Sao Paulo Symphony Orchestra, which, in 2012 introduced a new conductor, Marin Alsop, and did the most important European tour of orchestra’s history.

You wrote about their concert at the BBC Proms, and I would like to interview you about it, about how the European critics sees a Brazilian orchestra on the rise in Europe and how could Marin Alsop raise them to a higher level of quality. If you accept to talk to me, I can send you some questions by e-mail. My e-mail is jonas.lopes@abril.com.br

Thank you very much.

Best,