As the reviews came trickling in yesterday of Monday night’s Julietta at ENO, I have to admit to

wondering if I had just been in the wrong mood, or just hadn’t got where the

greatness of Martinů’s ‘rarely performed masterpiece’ lay. Indeed, was I just

being too cynical in detecting a certain irreconcilable contradiction at the

heart of such marketing rubric? Isn’t it often the case that many of these ‘masterpieces’ rely on their very status as ‘rarely performed’, giving their

champions the convenient riposte: ‘well, you can never really judge it unless

you see it in a decent staging’.

Well, Julietta has

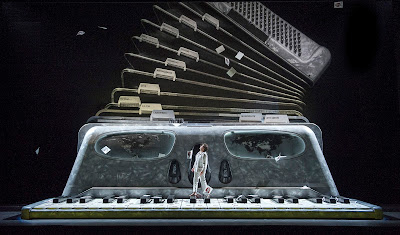

now definitely received that at ENO, with Richard Jones turning in a typically stylish

production—although was I alone in wondering whether, beyond its striking,

stretched and manipulated giant accordion, there wasn’t room for more in the

way of dreamy imagination? The fine cast did an excellent job, the orchestra,

too. And, while I should declare that Monday night was the first time I heard the

score, it seemed as though Ed Gardner made a persuasive case for it: its

splashes of glittering colour came across well, as did the lyrical

outbursts, some of which came close to sweeping me along.

|

| From left to right: Emelie Renard, Clare Presland and Samantha Price as the Gentlemen and Peter Hoare as Michel (Photo: Richard Hubert Smith) |

But the work, based on a surreal play by Georges Neveux,

left me entirely cold. It is neither terribly funny, nor, to our (or my, at least) jaded

21st-century imaginations, terribly interesting. An exploration of a community

floating around in a state of collective amnesia has possibilities for highlighting humour

or a sort of nightmarish, recurring futility, neither of which were explored. Meanwhile,

the work’s leaden pace—lingering on matters with which, by definition, it is

difficult for the audience to engage in any meaningful way—made the 50 minutes

of Act 2, in particular, seem extremely long.

It measures pretty low on the surrealism scale, in any case, and suffers by not employing the sort of snappy pace—a playful, light engagement with time that deals in seconds rather than minutes—that would seem to be part and parcel of the aesthetic, where one flitting absurdity dissolves into the next before the brain has a chance to pin it down and destroy it with logic. A work that came to mind was Shostakovich’s The Nose—hardly a masterpiece, but a piece whose increasingly ridiculous scenes are rattled through at such a pace that they never overstay their welcome. And, of course, we can only have a fragmentary, patchy idea of the actual romance between Julietta and Michel, a travelling salesman who arrives in the strange amnesiac town with the advantage of a memory—an advantage that he, too, finally loses.

It measures pretty low on the surrealism scale, in any case, and suffers by not employing the sort of snappy pace—a playful, light engagement with time that deals in seconds rather than minutes—that would seem to be part and parcel of the aesthetic, where one flitting absurdity dissolves into the next before the brain has a chance to pin it down and destroy it with logic. A work that came to mind was Shostakovich’s The Nose—hardly a masterpiece, but a piece whose increasingly ridiculous scenes are rattled through at such a pace that they never overstay their welcome. And, of course, we can only have a fragmentary, patchy idea of the actual romance between Julietta and Michel, a travelling salesman who arrives in the strange amnesiac town with the advantage of a memory—an advantage that he, too, finally loses.

That’s clearly one of the work’s main points, but whether or

not it inspires deep contemplation or an eye-rolling sense of ‘so what?’ seems more

down to the individual than is often the case, as reviews ranging from five,

through four, to three stars would seem to make clear; from raves to what might

best be called non-raves. Martinů’s score, for its part, has some fine moments, and is put together with considerable skill; but it seemed to wheel out influences with too little input from the composer himself, and, for a work first performed in 1938, seemed distinctly behind the curve—a sense only emphasized by the fact that the production was being supported by

‘ENO’s Contemporary [!] Opera Group’. Still, there are plenty of opportunities for those who haven

’t seen it yet to make up their own minds.