|

| Photo: Mike Hoban |

But it's difficult not to feel that the production somehow pins the allegory--or the 'Morality', as Vaughan Williams designates it--down, restricting the Pilgrim's Everyman resonance. He becomes an allegorical character made specific, it seems, rather than a specific character made more allegorical.

But most of the debate looks set to revolve around Vaughan Williams's work itself. The composer admitted, the programme tells us, that the work was 'more ceremony than a drama'; he also admitted it was 'not "dramatic" and did not contain "a love story or any big duets"', but maintained that it was 'first and foremost a stage piece', which should not be 'relegated to the Cathedral'. But while the score contains some great music, the choral writing exultant and the orchestration sometimes brassy and assertive in a manner that can seem both threatening and comforting, the work seems to be preaching to those rather more converted--in all senses--than I feel I am.

And, above all, it's a piece that seems rather too comfortable in its moral position; although it has elements of the archetypal narrative of a journey beset with challenges leading to a goal, that goal seems too easily reached, those challenges--including the Fafner-like Appollyon, realized here with great theatrical panache but somewhat abstractly--too easily brushed aside. There is also something naively simplistic, it seems to me, about the straightforward 'wrongness' about those inhabitants of Vanity Fair, easily brushed aside in a world of black-and-white right and wrong (there's more genuine danger of temptation presented by one of Klingsor's Flower Maidens than all the pantomime-damery we were presented with here, slightly reminiscent, in retrospect, of the flamboyant othering that was necessary to safely neutralize homosexuality before it could be presented to prime-time TV audiences in the 70s and 80s).

And, above all, it's a piece that seems rather too comfortable in its moral position; although it has elements of the archetypal narrative of a journey beset with challenges leading to a goal, that goal seems too easily reached, those challenges--including the Fafner-like Appollyon, realized here with great theatrical panache but somewhat abstractly--too easily brushed aside. There is also something naively simplistic, it seems to me, about the straightforward 'wrongness' about those inhabitants of Vanity Fair, easily brushed aside in a world of black-and-white right and wrong (there's more genuine danger of temptation presented by one of Klingsor's Flower Maidens than all the pantomime-damery we were presented with here, slightly reminiscent, in retrospect, of the flamboyant othering that was necessary to safely neutralize homosexuality before it could be presented to prime-time TV audiences in the 70s and 80s).

|

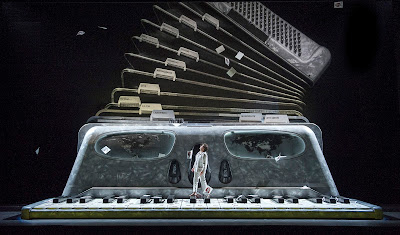

| Vanity Fair. Photo: Mike Hoban |

But what is also missing in most of Vaughan Williams' meditative, consoling score was the darkness, the obscurity, the cluttered agglomeration of emblems that theorists allegory--most famously Walter Benjamin--have seen as essential to the 'mode of the melancholic'. I can imagine there's a whole PhD thesis to be written about how Vaughan Williams's opera fits in with other 20th-century allegories, many of which were inspired exactly by the fragmentation attendant to modernism, the splintering of certainties into myriad uncertainties, the dissolution of grand meaning into multiple significations, which--if you'll excuse me steering the discussion onto an area of greater expertise--Hugo von Hofmannsthal's 'Lord Chandos' once used to be able to tame under the 'simplifying gaze of habit'. In fact, a comparison with Hofmannsthal is maybe not to stretch things too far; his fictional Chandos Letter, dated 1603 but written in 1902, pre-dates, as it were, Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress by over half a century. It certainly seems unlikely that a man so well-read as Hofmannsthal would be unacquainted with Bunyan's foundational work. (Evidence either way will no doubt be available in the volume of the critical edition of HvH's works that provides an annotated catalogue of his personal library).

But Hofmannsthal's own Jedermann, which takes the mediaeval English Everyman as its source which still opens the Salzburg Festival every year, is colourful (some might say ostentatiously Catholic) ceremony and drama--not least, perhaps, since it is staged on the steps of Salzburg Cathedral, as this trailer for the latest production demonstrates. But it has an ebullience to it that I missed in Vaughan Williams's more gentle Everyman work. (I imagine The Pilgrim's Progress, first performed at Covent Garden in 1951, had restorative aims behind it as the pre-WWI Jedermann, quickly pushed into service as centrepiece of the post-war Salzburg Festival).

But Hofmannsthal's own Jedermann, which takes the mediaeval English Everyman as its source which still opens the Salzburg Festival every year, is colourful (some might say ostentatiously Catholic) ceremony and drama--not least, perhaps, since it is staged on the steps of Salzburg Cathedral, as this trailer for the latest production demonstrates. But it has an ebullience to it that I missed in Vaughan Williams's more gentle Everyman work. (I imagine The Pilgrim's Progress, first performed at Covent Garden in 1951, had restorative aims behind it as the pre-WWI Jedermann, quickly pushed into service as centrepiece of the post-war Salzburg Festival).

Maybe I feel my spiritual home is nearer to Salzburg than it is to Bedford, where Bunyan's Pilgrim ostensibly sets out on his quest, or even London, the Celestial City he finally reaches. But I was also left a little unconvinced by the unusual dramaturgy of Vaughan Williams's work, particularly the second half, where there was a great deal more Pilgrim than Progress, and where the 'comic' interlude with Mr and Mrs By-Ends (despite the best efforts of Timothy Robinson and Ann Murray) provided scant relief.

It's a fascinating, strangely haunting work, but while it has some right not to be 'relegated to the cathedral'--or, like Jederman, the cathedral steps--it couldn't help make the Coliseum feel a little cathedral-like. And the work's religiosity, presented neither with the intoxicating sensuality of Parsifal nor as an evocative background to a more profane drama as it so often is in Italian opera, made me feel a little queasy.

+BARDA.jpg)